by Ariela

The curse of engaging in a craft that many other people have done for centuries before you is that it is hard to come up with something original. But the flip side is that it's hard to screw up in a totally original way, too.

Calligraphy has been around for millennia, and basically any cock-up that can be done has been. Moreover, we have terms for them! And many of them are in Greek, because lots of them were made by monks copying bibles.

There are lots of ways to screw up writing a text. For now, I will only deal with the ones that arise from unintentional mistakes made while copying a text by looking at a reference document (called the exemplar). A different set of mistakes can be made if you are writing out a text that is being read to you, or writing from memory. I will also only deal with errors that occur in languages based on alphabets that are written horizontally; there is some overlap with syllabic or ideographic writing and vertical writing, but each does have their own pitfalls.

All examples below use the text of Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley.

Haplography

This is when a scribe omits a chunk of text due to the eye skipping from one section to another. Dropping one letter by mistake is not haplography, it has to be more. There are several sub-types of haplography.

Homeo teleuton (also homeoteleuton): An eye-skip due to words or phrases having the same ending.

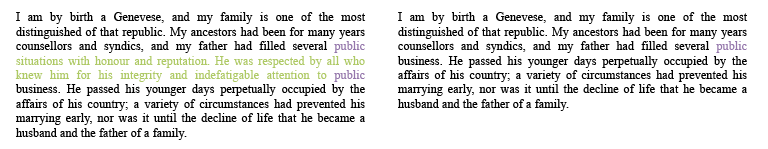

The word "child" is at the end of a phrase several times in this paragraph, leading to an eye jump from one instance to another. The text in purple is where the problem originates, and the text in green is omitted in the copy.

Homeo arcton (also homeoarchy): An eye skip due to words or phrases having the same beginning.

Here we have two sentences in short order that begin "There was a..." Jumping from the first to the second, we omit a bunch of text.

When the homeoarchy or homeoteleuton occurs at the beginning or end of a line, right up against the margin, it is a type of parablepsis.

Parablepsis is, according to Wiktionary, is "A circumstance in which a scribe miscopies text due to inadvertently looking to the side while copying, or accidentally skips over some of it." This is a bizarre definition, to my mind, as the punctuation seems to divide it into two completely disparate sets of errors: a) any type of error made due to looking to the side, or b) any omission of a bunch of text for any reason. I think a better definition would be "Haplography that occurs at the beginning or end of a line."

Here we have homeoteleuton that is also parablepsis: the word "public" appears at the end of two lines, and the eye skips from the first to the second.

Dittography

This is where you repeat a sequence. It can be anywhere in length from just a few letters to several lines, depending on how quickly you catch yourself.

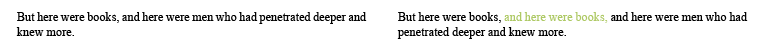

Here we have a phrase duplicated. This sort of dittography usually indicates that the scribe's mind wandered in the middle of the line.

Dittography mostly happens when there is a repetitive element in the text, but every once in a while a scribe would just have a total brain fart and reproduce something for no apparent reason.

There's no obvious reason why the line in green was written twice.

It can also happen anywhere within a text.

This is an example of dittography within one word. "Possessed" is written correctly in the original on the left, but has an extra "ess" in the copy on the right.

Transposition

This is where you switch the order of things.

It can cover the swapping of letters in a word.

Here we have a simple letter-order swap. If you just had the copy text on the right, you would probably be able to figure it out.

It also includes the flipping of word order.

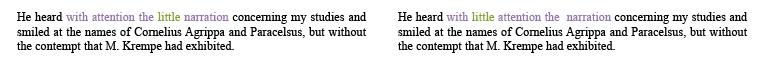

Two words are swapped around here. It makes some difference to the meaning of the text, but not a huge amount.

These are both fairly benign examples of transposition. The former is easily spotted and the latter doesn't change the text fundamentally. However, transposition can change the meaning of a text drastically if applied in the wrong place.

Changing the position of one word in this sentence changes its meaning completely.

As bad as this is, it can be much worse. English is a verbose language, and Shelley's writing style is flowery. In terse languages where word order matters (so not Esperanto, for example), moving a word around means greater disruption to the meaning imparted. In Hebrew, where words are generally shorter due to verb and noun constructs based on a three-letter root, swapping two letters can literally mean the difference between the words 'crisis' and 'meat' (שבר/בשר), 'evening' and 'hunger' (ערב/רעב), 'hate' and 'subject/thesis' (שונא/נושא). It is not always clear from context that a mistake occurred.

How to Prevent Scribal Errors

No matter how careful you are, it's almost impossible to copy out a text of great length without making any mistakes at all. In the 13 years I have been working as a professional calligrapher, I have only once written a text which my proofreader found to be completely without error. Fortunately for me, I do my calligraphy in pencil first, get it proofed, and then ink it after the corrections are made. (That's part of Terri's job.) Other scribes throughout history have not been so lucky. It is possible to fix a mistake made in ink, but the longer the mistake drags on, the harder it is. Also, errors of omission frequently don't leave enough room for fixing.

So the next time you see a tweet from us like this:

You'll know what happened.